1. Null Hypothesis (H0, pronounced as H-nought): The independent variable will not have an effect; there’s no difference between treatment group and control group.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): The independent variable has an effect.

When we try to confirm the hypothesis, we are statistically testing the Null Hypothesis. We assume H0 is true (there is no effect), then we try to prove that the assumption of no effect is very unlikely to happen, to reject the null.

2. Sampling Variation: Even if you have a 50% chance of flipping a coin for heads or tails, you won’t necessarily get 5 heads and 5 tails when you flip a coin 10 times. This is sampling variation. According to a null hypothesis, differences between variables is just this difference.

Theoretically, this possibility can never be excluded. So we can never be 100% sure H0 is not true. But we can estimate the probability of H0 being untrue.

3. If we keep drawing random samples of the same size from the same population, we’ll get a normal distribution of the means of the samples.

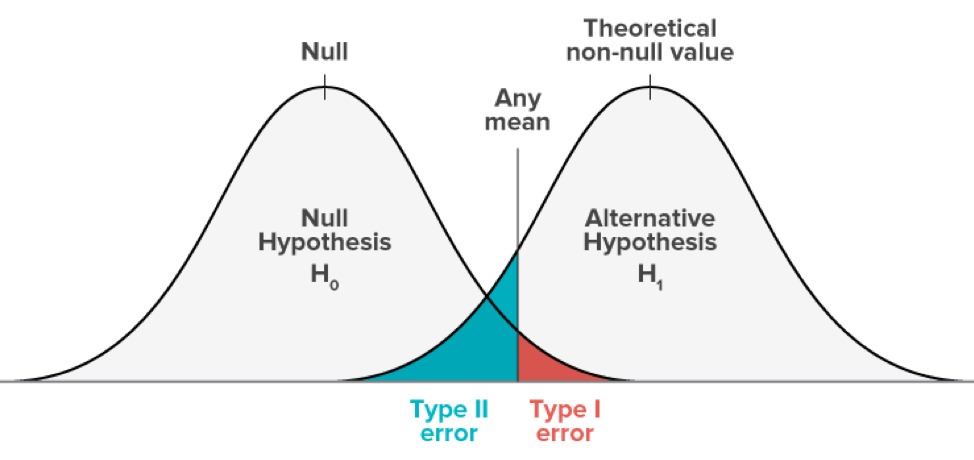

Greater overlap between null & sample distribution = greater chance of getting results by chance (greater chance of H0 being true).

4. Inferential statistics are used to answer “How different is different?” – how big of a difference between the means of our conditions we must observe before we conclude that the IV has an effect.

5. The alpha level is the amount of risk the researcher is willing to take to wrongly reject the H0. (We usually use α = .05)

p-value corresponds to the area of overlap between null distribution and sample distribution.

Image the two distributions completely overlap, then p = 1, accept H0 with the most confidence.

Therefore, when p <.05, we reject the null. There’s still 5% chance that the difference is caused by chance, so we might have wrongly rejected the H0, but this is the risk we’re willing to take.

When p>.05, we fail to reject the H0, because of insufficient evidence to reject.

6. Two types of errors:

- Type I error: we reject the null in a case when it is actually true. (We set it to be 5%). — We claim there’s effect when there’s isn’t.

- Type II error: we fail to reject the null even though it is false. — We claim there’s not effect when there’s is.